Every day in our practice we see horses of different breeds, sizes and body weights. With the high cost of feeding and maintaining a horse nowadays, we tend to keep our focus on the skinny rescue horses. But what about the opposite end of the spectrum? What about the overweight, “easy keeper” horse?

Most horse owners feel a little insulted whenever we mention that their horse might be a little overweight. We have clients that still bring it up years later. Please don’t take it personally! We’ve all had family members who use food as a way to express affection. The dinner table is always overflowing with food and if you did not eat everything, the food was not good and if you finished everything, then there was not enough! The same applies to our equine family members. We tend to shower them with apple treats, carrots and grain so they know how much they are loved and appreciated. We are not saying they don’t deserve our affection, or that we need to completely starve our horses. Moderation is the key and keeping a close eye on their body weight is as important as hoof care, vaccinations or teeth floating.

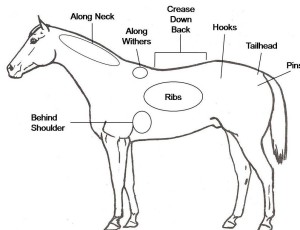

The Henneke Body Condition Scoring (BCS) chart allows us to standardize horses body condition within the profession. It is a 1 to 9 scale where 1 is skin and bones and 9 is severely obese. It bases the scale on certain points of fat accumulation of the horse’s body, more commonly on the neck, withers, behind the shoulder and over the ribs; as well as the rump and tail head.

The Henneke Body Condition Scoring (BCS) chart allows us to standardize horses body condition within the profession. It is a 1 to 9 scale where 1 is skin and bones and 9 is severely obese. It bases the scale on certain points of fat accumulation of the horse’s body, more commonly on the neck, withers, behind the shoulder and over the ribs; as well as the rump and tail head.

The higher the fat accumulation, the higher the number, where the ideal body condition is between a 4 and 6 out of 9. An easier way to remember is that you should be able to easily feel the ribs and palpate the spaces between them without actually seeing them.

What is the big deal if your horse is overweight? The answer is, lots of reasons! The overweight horse tends to be more prone to overheating due to the fat insulating their body. They tend to be exercise intolerant, easily becoming tired and winded. Just like us, the extra weight is hard on their joints and legs leading to lameness problems. But probably more important and concerning to veterinarians is the fact that overweight horses are more prone to laminitis and founder. This crippling condition can lead to permanent lameness and even sometimes euthanasia.

What do we do about it? It should be easy, right? Feed them less and exercise them more. Just like us, body weight is dependent on calories in and calories out. For most horses that will work fine. Just tweak the diet a little, decrease any supplements or grains, and increase the exercise daily. But what about the “easy keeper” that appears to gain weight on air? What about that horse that is a 7-9 BCS and is only on pasture? This is when it gets a little more complicated. Yes, if there is a large pasture that cannot be divided then the amount of time the horse has access to the pasture or the addition of a grazing muzzle to control the intake of grass might be enough.

When the amount of grass is minimal and overgrazed, the horse is not receiving any other caloric supplement, and we are still having problems keeping a healthy weight, that is when further diagnostics are needed to rule out a metabolic disease. The two most common endocrine metabolic diseases associated with overweight horses are Equine Metabolic Syndrome (EMS) and Cushing’s disease.

EMS is a disease of young to middle-aged horses that have a problem regulating their blood sugar level. They commonly have fat accumulation over abnormal areas, insulin resistance and are prone to laminitis. These horses used to be called “Cushinoid” because they look like Cushing’s horses but do not test positive for the disease and/or do not have the excess hair associated with Cushing’s disease. Horses with EMS are particularly sensitive to soluble sugars in their diet. They have a reduction in the ability of the hormone insulin to control blood sugar levels by transporting them into muscle, liver and fat cells in the body. This leads to an overproduction of insulin by the pancreas to compensate for the lack of function. Eventually the body is unable to keep up with the need and it leads to high levels of circulating sugars and insulin in the blood. This disease process is commonly compared to type II diabetes in humans.

On the other hand Cushing’s disease or more recently renamed Pituitary Pars Intermedia Dysfunction (PPID) is more commonly associated with older horses with shaggy hair coats that do not shed in the summer. At first it presents itself with similar symptoms as EMS (exercise intolerance, weight gain, fat deposition in abnormal places and laminitis); PPID horses will typically progress to developing muscle weakness on the top line and a long shaggy hair coat that often fails to shed in the summer. Cushing’s is more commonly associated with middle aged to older horses and ponies and is caused by a growth on the pituitary gland of the horse. This growth produces an increase in the production of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which in turn leads to an increase in the release of the stress hormone cortisol from the adrenal glands which is in charge of many normal body processes, but in excess levels leads to the clinical signs associated with PPID in the horse.

On the other hand Cushing’s disease or more recently renamed Pituitary Pars Intermedia Dysfunction (PPID) is more commonly associated with older horses with shaggy hair coats that do not shed in the summer. At first it presents itself with similar symptoms as EMS (exercise intolerance, weight gain, fat deposition in abnormal places and laminitis); PPID horses will typically progress to developing muscle weakness on the top line and a long shaggy hair coat that often fails to shed in the summer. Cushing’s is more commonly associated with middle aged to older horses and ponies and is caused by a growth on the pituitary gland of the horse. This growth produces an increase in the production of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which in turn leads to an increase in the release of the stress hormone cortisol from the adrenal glands which is in charge of many normal body processes, but in excess levels leads to the clinical signs associated with PPID in the horse.

Diagnosis of both diseases is based on clinical signs and evaluating systemic levels of the individual hormones. EMS horses have an increased fasting insulin level and normal to increased blood glucose levels indicating the increased need for insulin production to maintain normal glucose levels. In the early stages of the disease, the results might be inconclusive with insulin levels still within range, but the clinical picture supporting the diagnosis. In such cases an oral glucose test will be more diagnostic where insulin response to a sugar solution administered by mouth is measured at specific intervals. PPID used to be diagnosed by administering a steroid and evaluating the change in cortisol levels in response to the drug. Because of the normal changes in cortisol levels during the day and the potential for laminitis with steroid administration, testing was inconsistent and not often performed. Now, ACTH levels in blood are considered a reliable indicator of PPID. Still affected by seasonal variations, most labs are accounting for the changes by adjusting the reference ranges.

Treatment of EMS is focused at decreasing insulin levels and body weight to in turn decrease the likelihood of laminitis. Primary treatment is always focused on diet and exercise. Decreasing access to soluble sugars, whether from pasture or supplements or soaking hay, and an increase in exercise is going to increase sensitivity to insulin in the body. For the horses that diet and exercise is not enough, then high doses of Thyroid hormone supplementation can promote a hyperthyroid condition leading to increased metabolism and weight loss. We also sometimes use human diabetes medications that increase insulin sensitivity, such as Metformin. Metformin can be used in refractory cases, or for horses suffering from laminitis, where exercise is not an option.

Treatment of PPID is also focused on weight and diet, but on older horses a focus on systemic health and preventative medicine is key. Horses with PPID tend to be immunosupressed and prone to infections, particularly dental disease, so routine exams and dental care are important. They also have problems controlling their own temperature so extra care must be taken on days with extreme weather changes. Urination is often increased, so it is important to provide plenty of fresh water at all times. Pergolide (Prascend®) is the drug of choice to treat PPID working by down-regulating the production of hormones from the pituitary gland and improving clinical signs in over 75% of cases. Previously we used compounded Pergolide, but recent studies have shown that the compounded version is unstable and often does not provide an adequate dose.

To complicate the diagnostic challenge, it is estimated that over 1/3 of horses with PPID also suffer from EMS; and younger horses with EMS are at a higher risk of developing PPID at an older age. Every year our ability to diagnose these diseases improves and what we know about how to treat them changes. The important part is to recognize the changes in your horse early and consult with your veterinarian about the next step in diagnostics and treatment.