In the last couple of months it seems like the word laminitis has been mentioned almost daily around the clinic. Commonly known as “founder,” it is a dreaded, often life threatening disease that can be career ending and permanently crippling. Recent studies consider laminitis a leading cause of death among horses, surpassed only by colic. Even though most cases are not fatal, they can permanently affect the usefulness of the horse and cause permanent soundness problems as well as management headaches. It is estimated that up to 15% of all horses will suffer from a certain degree of laminitis in their lifetime. Here in the Pacific Northwest, during spring and fall, those numbers seem significantly higher.

In the last couple of months it seems like the word laminitis has been mentioned almost daily around the clinic. Commonly known as “founder,” it is a dreaded, often life threatening disease that can be career ending and permanently crippling. Recent studies consider laminitis a leading cause of death among horses, surpassed only by colic. Even though most cases are not fatal, they can permanently affect the usefulness of the horse and cause permanent soundness problems as well as management headaches. It is estimated that up to 15% of all horses will suffer from a certain degree of laminitis in their lifetime. Here in the Pacific Northwest, during spring and fall, those numbers seem significantly higher.

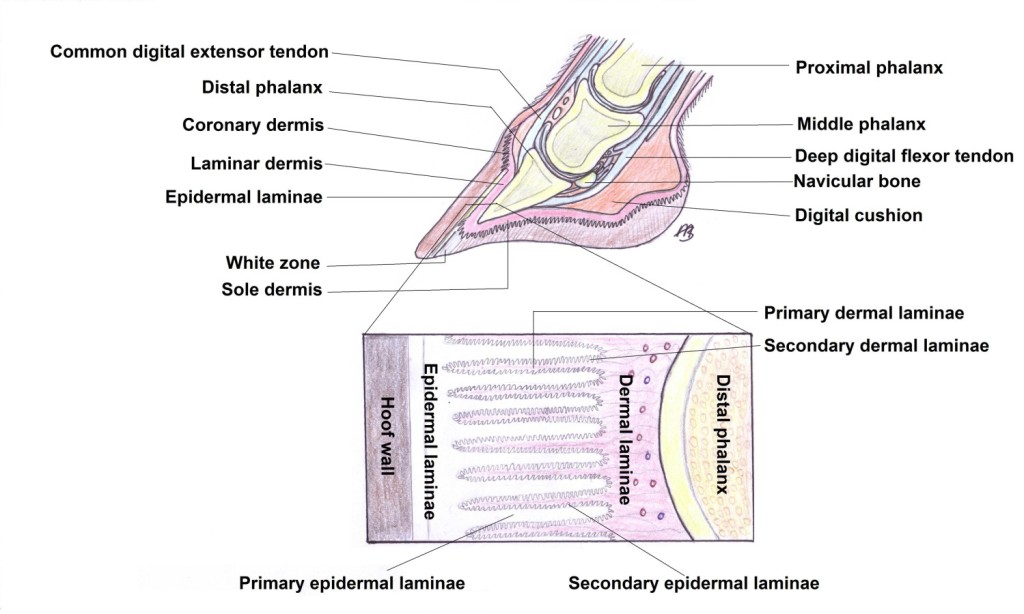

In the simplest of terms, laminitis is inflammation of the laminar attachment of the hoof wall to the coffin bone. By design, horses are standing on the nail of one finger leading to, in the average size horse, a distribution of 1,000 pounds between four nails. At times, a horse’s gait can make them distribute all this weight into a single digit causing an extreme amount of strain into the supporting structures. The bony column is attached to the hoof wall by a series of finger like projections called laminae that intertwine with each other like pages in a book. Each hoof contains an average of 500 to 600 primary laminae with each of those primary laminae containing an additional 150 to 200 secondary laminae arranged in an architecture similar to the branches and leaves of a tree. This arrangement provides for a large surface area that supports the weight of the horse to the hoof capsule as well as providing shock absorption during weightbearing exercise.

Although as a profession we do not completely understand all the specifics of the laminitic process or how to prevent it, we do know that usually a primary insult leads to inflammation of the lamellar structure of the hoof. These tightly arranged structures get inflamed which leads to a weakening of the attachment between the coffin bone and the hoof wall. This loss of strength compounded by the weight of the horse pushing down on this tissues and the flexor tendon pulling the coffin bone away from the hoof wall leads to separation of these structures.

As the laminae weaken and release, the coffin bone can rotate and/or sink down towards the ground leading to the common name of the disease “founder” since the tip of the coffin bone rotates towards the ground. These changes in anatomy can lead to external changes to the hoof wall. Early changes can be characterized by growth rings on the hoof wall. Severe changes like overgrowth of heel and lack of growth at the dorsal hoof wall can lead to “elf like” feet associated with chronic, end stage laminitis. These horses are also prone to multiple foot abscesses, seedy toes and white line separation. The most important step in this disease is diagnosis. The earlier the signs are recognized and changes detected, the quicker appropriate treatment and trimming/shoeing changes can be implemented to help prevent permanent damage to the architecture of the hoof.

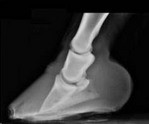

The most common signs of laminitis include an acute onset of lameness, most commonly in the front limbs. It can also occur on one limb, hind limbs or all four limbs simultaneously. Symptoms include a reluctance to move, shifting weight in the front limbs, front limbs camped out in front while hind limbs are placed under the body in an attempt to distribute the weight to the unaffected legs. The affected hoof or hooves are usually hot on palpation (to the touch) and have increased digital pulses indicating an increase in blood supply consistent with inflammation. When forced to move, the horse tends to land heel first to protect the toe and usually looks more sore on hard ground or when forced to turn to the affected side. A diagnosis of laminitis can only be confirmed with a thorough lameness exam that demonstrates pain on the sole and toe area. Radiographs (“x-rays”) of the affected feet are always needed to confirm the separation and determine the degree of rotation, if any, of the coffin bone. This information is essential for planning a course of treatment and to provide necessary information for the farrier as to the degree of change and the new angles necessary to slow down the disease and achieve some level of comfort for the horse.

The most common signs of laminitis include an acute onset of lameness, most commonly in the front limbs. It can also occur on one limb, hind limbs or all four limbs simultaneously. Symptoms include a reluctance to move, shifting weight in the front limbs, front limbs camped out in front while hind limbs are placed under the body in an attempt to distribute the weight to the unaffected legs. The affected hoof or hooves are usually hot on palpation (to the touch) and have increased digital pulses indicating an increase in blood supply consistent with inflammation. When forced to move, the horse tends to land heel first to protect the toe and usually looks more sore on hard ground or when forced to turn to the affected side. A diagnosis of laminitis can only be confirmed with a thorough lameness exam that demonstrates pain on the sole and toe area. Radiographs (“x-rays”) of the affected feet are always needed to confirm the separation and determine the degree of rotation, if any, of the coffin bone. This information is essential for planning a course of treatment and to provide necessary information for the farrier as to the degree of change and the new angles necessary to slow down the disease and achieve some level of comfort for the horse.

In the early stages of the disease, treatment is focused on controlling inflammation and pain and providing support to the bony column to prevent further rotation and/or sinking of the coffin bone. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs like Phenylbutazone (Bute), Flunixin meglumine (Banamine) or Firocoxib (Equioxx) are prescribed to control further inflammation of the laminae. Cryotherapy, ice water therapy, helps to lower the temperature of the hooves and slow down the disease process while providing some pain control. Strict stall rest and hoof support are essential to slow down further separation of the coffin bone from the hoof wall. Support pads or boots that distribute the weight towards the frog and the distal structures of the hoof and away from the sole work to reinforce the bony column while providing comfort and mechanical support.

After the acute phase, regular trimming is required to backup the dorsal hoof wall to decrease the leverage pulling away from the coffin bone. Supporting the back of the foot with specially de-signed shoes can provide comfort and prevent damage on the later stages of the disease. Veterinarians and farriers struggle with the type of shoe/support to use for each particular horse. The best approach involves trial and error with everybody involved remaining open to suggestions. There is no set formula on how to get a laminitic horse comfortable; each horse responds differently and we need to listen to the horse and adjust our plan accordingly.

Although not completely understood, we recognize multiple causes of laminitis. Some are straightforward like support limb laminitis where one leg is injured and the opposite limb carries too much weight leading to laminitis. Traumatic laminitis, commonly known as “road founder,” is where over use or hard surfaces lead to the inflammation. More complicated cases like a systemic toxic event, can lead to laminitis as well. For example, horses with diarrhea, cases of grain overload or mares with retained placentas or uterine infections where bacteria travels through the blood stream causing a septic shower and subsequent inflammation. Perhaps the most recognized and sometimes misunderstood cases are caused by endocrine diseases. These are the “grass founder” cases on horses that are easy keepers or those that have been diagnosed as insulin resistant.

Horses with Equine Metabolic Syndrome, Cushing’s Disease or pituitary dysfunction are the most common cause of laminitis in the Northwest. This group includes the spring and fall grass laminitis horses in Oregon, when the lush green growing grass is stressed by cold nights and overgrazing leads to an increase in soluble carbohydrates and fructans in the leaves of grass. Other less common causes of laminitis like severe fevers, hoof infections, black walnut exposure or cellulitis are also recognized. Any of these conditions when aggravated by long toes and lack of routine hoof care or obesity, will mechanically provide a perfect environment for laminar inflammation. The longer the toes, the longer the break over so more pressure is applied to the flexor tendons for proper locomotion. This transfers to increased tension on the laminar supporting structure and easier separation.

A prompt diagnosis made by identifying the signs of laminitis and veterinary diagnostics like radiographs at an early stage of the disease will significantly improve our chances of a good outcome. Early and aggressive treatment with antiinflammatory drugs and cryotherapy, as well as diet changes when appropriate, can make the difference between minimal to no rotation and a life-threatening disease. Above all, a clear and a open line of communication between owner, veterinarian, and farrier can make the difference in the prognosis in this often fatal and frustrating disease of horses.

A prompt diagnosis made by identifying the signs of laminitis and veterinary diagnostics like radiographs at an early stage of the disease will significantly improve our chances of a good outcome. Early and aggressive treatment with antiinflammatory drugs and cryotherapy, as well as diet changes when appropriate, can make the difference between minimal to no rotation and a life-threatening disease. Above all, a clear and a open line of communication between owner, veterinarian, and farrier can make the difference in the prognosis in this often fatal and frustrating disease of horses.